Whether you’re a traveling executive or an assistant managing the movements of a high-level traveler, situational awareness is one of the basic building blocks of personal safety.

Travel—no matter how carefully executed—involves risk. Auto accidents and medical emergencies occur on the road, just as they do at home. The risk of targeted and opportunistic crime is also a consideration for high-profile travelers, whose appearance and patterns of movement may signal potential to a bad actor.

Situational awareness is one of the best tools in your arsenal for mitigating these risks. And while it’s useful in regular, day-to-day situations, it is particularly useful in unfamiliar environments. Both the Cooper’s Color Code and Savoya’s STOP model can help.

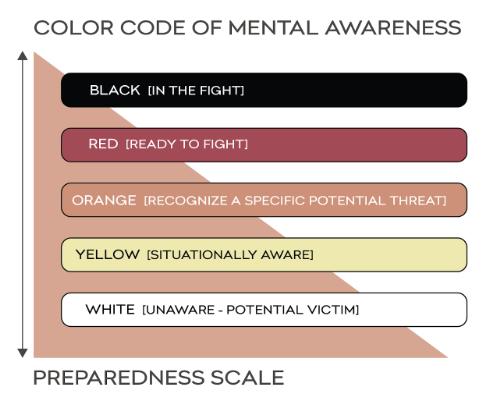

Cooper’s Color Code is a situational awareness framework developed by Jeff Cooper, a United States Marine and pioneering firearms instructor. The system—which he originally developed to train law enforcement officers—describes the four stages of readiness to take lethal action against a threat, ranging from an unprepared “White” condition to an active combat “Red” state.

Personal protection leaders have since adapted Cooper’s Color Code to apply more broadly to situational awareness in general, in addition to one’s readiness to fight.

In this iteration:

As a general rule, this interpretation of Cooper’s Color Code recommends “living in yellow,” which is a great rule of thumb for travelers. Living in yellow means you are present in the moment and actively observing your surroundings with all five senses. You are vigilant but not paranoid—just maintaining a relaxed awareness of the world around you.

To see why this is so important, take a look at the image below from the Boston Marathon Bombing:

Despite the fact that an out-of-the-ordinary situation is occurring—the presence of an unidentified explosive device—the people standing near the device have no awareness of it. They are distracted by the runners, taking photos with their phones, and chatting with the people standing next to them. “Living in yellow” would have helped these bystanders recognize that there was an unclaimed bag sitting at their feet.

In the image below, the officer in the right hand corner is in an “Orange” state. He’s identified a specific, out-of-pattern threat that has occurred, and is preparing to respond.

Carrying the example further, the runners and bystanders who are running away from the explosion are in a “Red” state, where they are acting to avoid or address an identified threat. They aren’t panicked; they’re focused and powerful. They may be experiencing the feeling of “fight or flight,” but they know what they’re going to do in response to the situation in this condition.

Conversely, those in whom the explosions triggered a “Black” state were frozen in fear. Despite the chaos happening around them, they remained in place—unable to mentally process the next steps that should be taken.

Remaining in red or black for too long is obviously undesirable, as it means danger is present. While orange might seem like a better alternative, it actually veers quickly into paranoia. In fact, maintaining this hyper-vigilant state can actually blind you to real threats occurring around you—which you have an opportunity to observe and evaluate when you’re a calmer yellow.

Using Cooper’s Color Code on a daily basis becomes second nature for law enforcement professionals, who may be called into life or death decisions at any moment. But maintaining this level of awareness isn’t always easy for executive travelers. For instance, if it’s known that an executive will be distracted—perhaps because they’re entertaining a guest or participating in an event—it may make sense to send another person (as in, a colleague or protector) who can stay alert.

Another tool that can help is Savoya’s STOP model.

Rather than requiring that travelers maintain continual awareness, the STOP model is based off a trigger that periodically reminds executives to engage with their surroundings. In this case, every time your executive sees a stop sign, they should:

If you or your executives will be traveling in an area where they won’t encounter many stop signs (for instance, if they’ll be inside all day at a business convention), rework this model around a more common trigger. The item itself prompting the review isn’t what’s important. What’s critical is regularly pausing to evaluate the situation and maintain an appropriate level of awareness, based on what you find.

Both of the frameworks above are useful tools for maintaining situational awareness, but they won’t do you any good if you forget them immediately after clicking away from this article.

Instead, commit to practicing the system that makes the most sense to you on a regular basis. If you can make a habit out of flexing your situational awareness muscles during your everyday routines, you’ll be much better prepared to draw on these skills when you need them to stay safe in an unfamiliar environment.